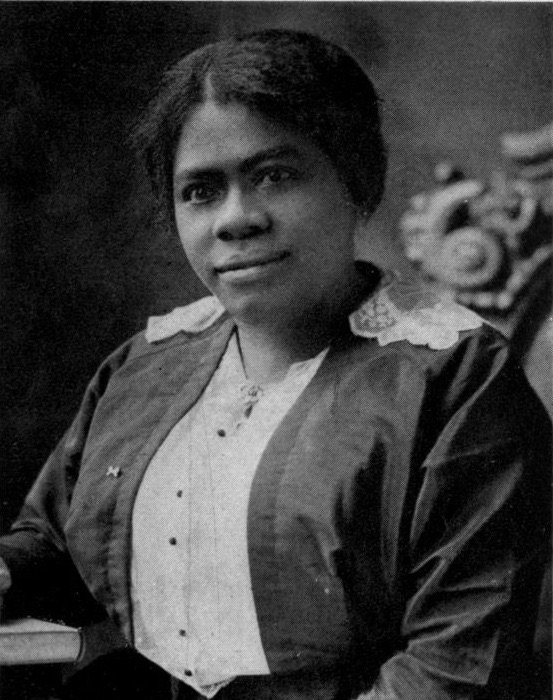

The first African-American Congresswoman and first black candidate on a major party’s presidential ticket, Shirley Chisholm was catapulted into the national limelight by virtue of her race, gender, and will to create a more inclusive government. The trailblazing Congresswoman once said, “If they don’t give you a seat at the table, bring a folding chair” – a phrase that has since served as a mantra and rallying cry for many Americans.

Shirley Anita St. Hill Chisholm was born in Brooklyn, NY to immigrant parents in 1924. Her father was a factory worker who came from Guyana and her mother was a seamstress from Barbados. She earned multiple degrees in education from Brooklyn College and Columbia University.

After college, Chisholm became a nursery school teacher and she also earned her master’s degree from Columbia University at the same time. She was ready to fight racial and gender inequality in the U.S. and became a community activist through several organizations. She was a leader in League of Women Voters, National Association for the Advancement for Colored People (NAACP), Urban League, and Democratic Party Club in Brooklyn.

Chisholm became interested in politics after she worked as a consultant on child care policy for the City of New York. She ran for the State Legislature in New York in 1964. After winning that election, she served for four years. In 1968, a lawsuit brought under the Voting Rights Act ordered that New York redraw districts to more fairly represent Chisholm’s majority black and Jewish neighborhood. She ran for the House of Representatives without the support of party leadership, but won her seat anyway.

Her motto and title of her autobiography—Unbossed and Unbought—illustrated her outspoken advocacy for women and minorities during her seven terms in the U.S. House of Representatives. In Congress, she used her knowledge and background to introduce more than 50 pieces of legislation focused on the needs of women, children, immigrants, those with low income, and people of color. She was a co-founder of the National Women’s Political Caucus and the Congressional Black Caucus in 1971. After gaining influence in the House, she became the first black woman to serve on the powerful Rules Committee.

Chisholm then announced her bid to become President of the United States, calling her campaign the “Chisholm Trail.” However, discrimination followed Chisholm’s quest for the 1972 Democratic Party presidential nomination. Chisholm survived several assassination attempts during her campaign and refused to be intimidated into dropping out of the race. She was blocked from participating in televised primary debates, and after taking legal action, was permitted to make just one speech. She also suffered from an under-financed campaign and lack of support from the predominantly male Congressional Black Caucus. At the 1972 Democratic National Convention, she lost the bid for the presidency to Senator McGovern.

After leaving Congress in January 1983, Chisholm helped cofound the National Political Congress of Black Women and campaigned for Jesse Jackson’s presidential bids in 1984 and 1988. She also taught at Mt. Holyoke College in 1983. Though nominated as U.S. Ambassador to Jamaica by President Bill Clinton, Chisholm declined due to ill health. She died on January 1, 2005. Of her legacy, Chisholm said, “I want to be remembered as a woman … who dared to be a catalyst of change.”